Guy Fawkes (13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes, the name he adopted while fighting for the Spanish in the Low Countries,[1][2] belonged to a group of Catholic restorationists from England who planned the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.[3] Their aim was to displace Protestant rule by blowing up the Houses of Parliament while King James I and the entire Protestant, and even most of the Catholic, aristocracy and nobility were inside. The conspirators saw this as a necessary reaction to the systematic discrimination against English Catholics.

Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren (20 October 1632 – 25 February 1723) was one of the best known and highest acclaimed English architects in history,[1] responsible for rebuilding 55 churches in the City of London after the Great Fire in 1666, including his masterpiece St Paul's Cathedral, completed in 1710.

Educated in Latin and Aristotelian physics at the University of Oxford, Wren was a notable astronomer, geometer, mathematician-physicist as well as an architect. He was a founder of the Royal Society (president 1680–82), and his scientific work was highly regarded by Sir Isaac Newton and Blaise Pascal.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver

Oliver Cromwell was born into a family which was for a time one of the

wealthiest and most influential in the area.

Educated

at Huntingdon grammar school , now the Cromwell Museum, and at Cambridge

University, he became a minor East Anglian landowner. He made a living

by farming and collecting rents, first in his native Huntingdon, then

from 1631 in St Ives and from 1636 in Ely. Cromwell's inheritances from

his father, who died in 1617, and later from a maternal uncle were not

great, his income was modest and he had to support an expanding family -

widowed mother, wife and eight children. He ranked near the bottom of

the landed elite, the landowning class often labelled 'the gentry' which

dominated the social and political life of the county. Until 1640 he

played only a small role in local administration and no significant role

in national politics. It was the civil wars of the 1640s which lifted

Cromwell from obscurity to power.

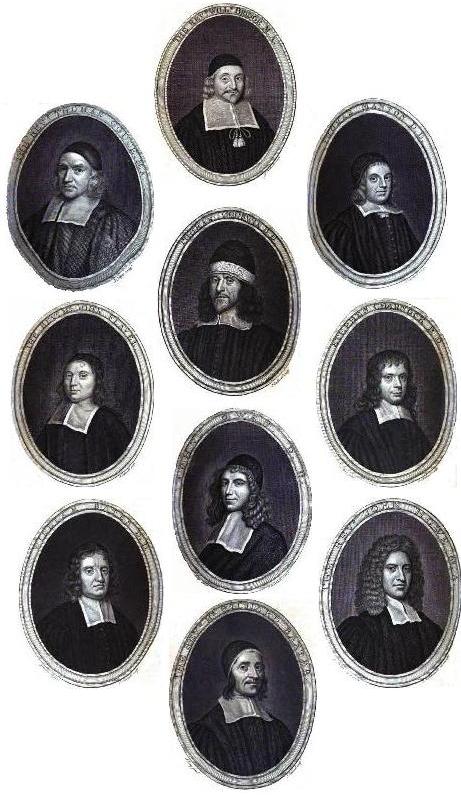

Puritans

A Puritan of 16th and 17th-century England was an associate of any number of religious groups advocating for more "purity" of worship and doctrine, as well as personal and group piety. Puritans felt that the English Reformation had not gone far enough, and that the Church of England was tolerant of practices which they associated with the Catholic Church.

The word "Puritan" was originally an alternate term for "Cathar" and

was a pejorative term used to characterize them as extremists similar

to the Cathari of France. The term "Puritans" roughly corresponds with Luther's term Schwärmer. Because the Puritans were under the influence of radicals critical of Zwingli in Zurich and Calvin in Geneva, they seldom cooperated with Presbyterians

in England. Instead, many advocated for separation from all other

Christians, in favor of gathered churches under autonomous Puritan

control.

Currently, the designation "Puritan" is often expanded to mean any

very conservative Protestant, or even more broadly, to evangelicals.

Thus, scholars commonly use the term Presisianist in regard to the historical groups of England and New England.[1]

Background

The Puritans' movement can be traced back to the Anabaptists of the

continent, although the term "Puritan" was not coined until the 1560s,

when it appears as a term of abuse for those who proposed further

reforms than those adopted by the Reformed Elizabethan Religious Settlement of 1559. Throughout the reign of Elizabeth I,

the Puritan movement involved both a political and a social component.

Politically, the movement attempted, mostly unsuccessfully, to have

Parliament pass legislation to replace episcopacy with Congregationalism, and to alter the 1559 Book of Common Prayer

to remove elements considered odious by Anabaptists. Like Anabaptists

on the continent, the Puritan movement called for a greater commitment

to Jesus Christ

for greater levels of personal holiness. By the end of Elizabeth's

reign, the Puritans constituted a distinct social group within the

Church of England who regarded themselves as the godly; they held out little hope for their neighbours who remained attached to "popish superstitions" and worldliness. Most Puritans were non-Separating Puritans who remained within the Church of England, and only a small number of Puritans became Separating Puritans or Separatists who left the Church of England altogether. Although the Puritan movement was occasionally subjected to suppression by the bishops

of the Church of England, in many places, individual ministers were

able to omit disliked portions of the Book of Common Prayer and to be

especially attentive to the needs of the godly.

Conflicts with Anglican Church

The Church of England as a whole was Calvinist, as seen in the Calvinist 39 Articles, the Calvinist Anglican Homilies, and in John Calvin's correspondence with King Edward VI and Thomas Cranmer. The Puritan movement was distinctive from the rest of the church in theology more prescriptive[jargon] than Calvinism, in legalism, theonomy[jargon], and especially – congregationalism. Charles I became king and was determined to eliminate the "excesses" of Puritanism from the Church of England. His close advisor, William Laud, who became Archbishop of Canterbury

in 1633, moved the Church of England away from Puritanism, rigorously

enforcing the law against ministers who schismatically deviated from

the Book of Common Prayer or who violated the ban on preaching about predestination.

Puritans opposed much of the Calvinist summations in the Church of England, notably the Book of Common Prayer,

but also the use of non-secular vestments (cap and gown) during

services, the use of the Holy Cross during baptism, and kneeling during

the sacrament.[1] Puritans rejected anything they thought was reminiscent of the Pope,

and many of the non-secular rituals preserved by the Church of England

were not only considered to be objectionable, but were believed to put

one's immortal soul in peril. While the Puritans under the rule of King James I of England

attempted to make peaceful reform of the English church, James viewed

their religious beliefs as close to heresy, and their denial of the Divine Right of Kings as potentially treasonous.